MLL2

,

AR

,

FOXA1

, and

APC

, were recurrently mutated. Clonal

mutations adjusted for CNVs were used to assess the

fraction of ctDNA in the cfDNA (average 0.39, range 0.067–

0.76, Supplementary Table 2). The ctDNA fraction correlated

with CTC enumeration via CellSearch (

r

= 0.54,

p

= 0.0037).

The use of paired-end sequencing allowed us to identify

structural variants commonly present in prostate cancer

[26]via split read and discordant read analysis (Supple-

mentary Fig. 4). A previously published algorithm

[27]was

applied in parallel with an in-house approach for calling and

visualising variants to minimise false positives. Intra-AR

structural variation was detected in 17/33 profiled cfDNA

samples, representing all four classes of structural variants

as exemplified by selected events in

Fig. 2 .Patient #4120

carried a deletion overlapping the ligand-binding domain

(LBD;

Fig. 2 A), with independent support provided by

calling CNVs based on coverage information (Supplemen-

tary Fig. 5A). Patient #4118 carried an inversion that flipped

the entire LBD

( Fig. 2 B). Patient #3843 harboured an 18-

Mb tandem duplication, originating in intron 1 of the AR

( Fig. 2C). However, the low-pass whole-genome sequencing

data for chromosome X suggest a more complex event

whereby spatially distant regions of the AR may have

merged (Supplementary Fig. 5B). In addition, for patient

#4038 a translocation removed the LBD, fusing chromo-

some X to a gene desert of chromosome 16

( Fig. 2 D).

Surprisingly, the majority of cfDNA samples with intra-AR

structural variants harboured multiple AR events (11/17,

Fig. 3 ), with focal alterations frequently affecting either the

cryptic exon region or the LBD.

To determine the expression of ARVs directly from CTCs,

we developed and validated an RNA-seq approach (Supple-

mentary Fig. 6). To verify the presence of CTCs, conventional

CellSearch processingwas performed to count the number of

CTCs per 7.5 ml of blood. In total, 28/34 (82.3%) blood

samples had detectable CTCs (median 72, IQR 15–239). This

allowed us to infer expression of full-length AR and seven

isoforms (AR45, AR-V1, AR-V2, AR-V3, AR-V5, AR-V7, and

AR-V9). Fourteen out of 15 unique patients with intra-AR

structural events expressed ARVs (Supplementary Fig. 7),

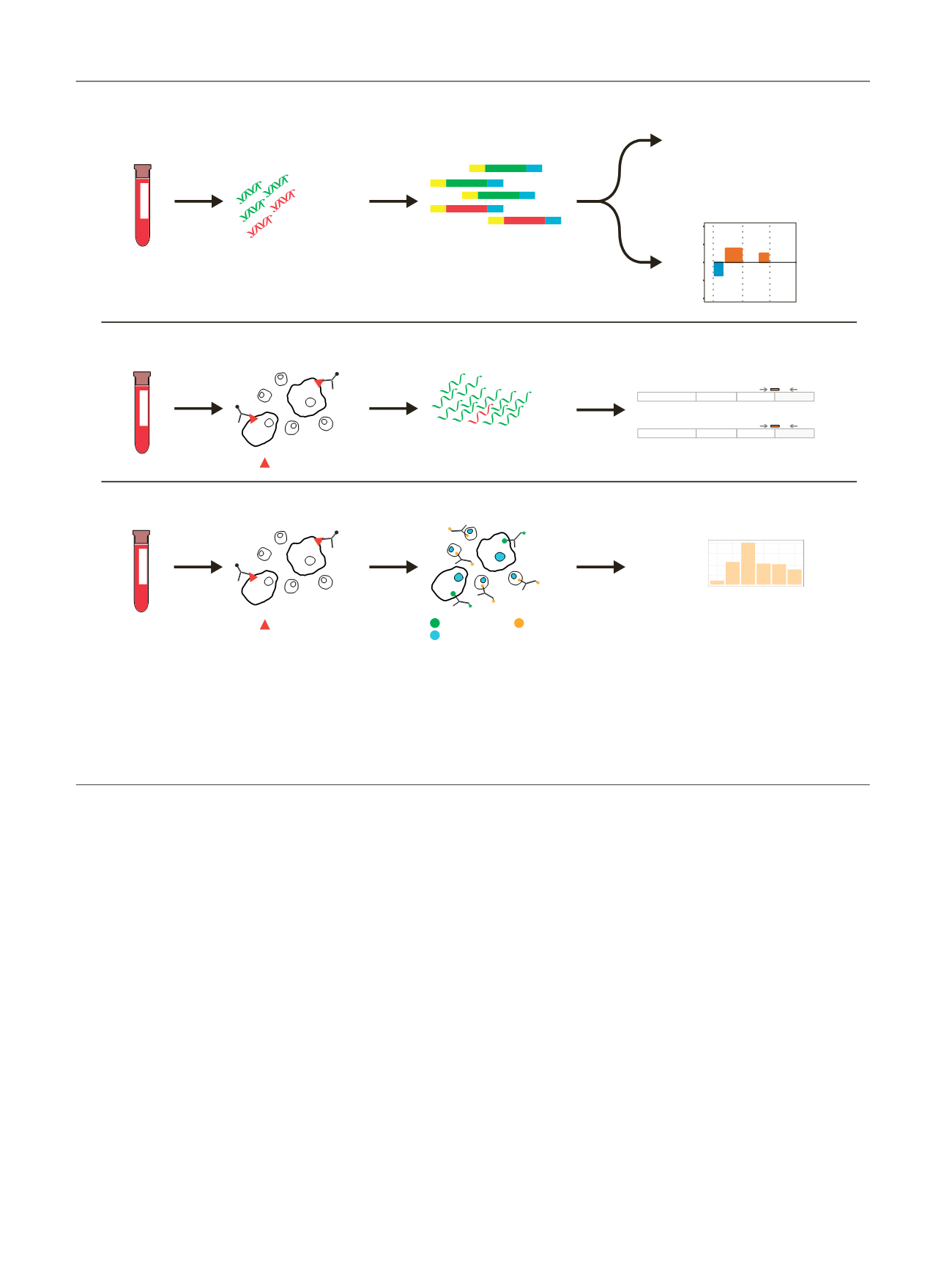

[(Fig._1)TD$FIG]

Draw blood

Normal DNA

Tumor DNA

Extract cell-free DNA

Targeted sequencing

TP53 mutation

SPOP mutation

Intronic AR deletion

etc

CITRATE

Low-pass WGS

8 9 10

−2

−1

0

1

2

Chromosome

Log2 Ratio

CellSave

EDTA

Circulating tumour

cell enrichment

AR exon-junction RNAseq

Cytokeratin CD45

Dapi

1

2

3

CE3

AR-V7

1

2

3

CE5

AR-V9

etc

EpCAM

Library prep

Normal RNA

Tumor RNA

Extract total RNA

5

25

200

1000

Nbr CTCs

Patient ID

Circulating tumour

cell enrichment

Counting CTCs

Draw blood

Draw blood

EpCAM

Labelling & staining

A)

B)

C)

Fig. 1 – Multilevel analysis of liquid biopsies. Circulating tumour DNA and AR splice variant expression were analysed in liquid biopsy samples. (A) Cell-

free DNA was extracted from plasma. Library preparation was subsequently performed, preparing the cell-free DNA for Illumina sequencing. Illumina

adapters are displayed with yellow or blue colours. Each DNA library was used for both targeted sequencing and low-pass whole-genome sequencing.

Targeted sequencing was applied to (1) detect mutations in genes commonly mutated in prostate cancer and (2) investigate the presence of intra-AR

structural variation. Low-pass whole-genome sequencing was performed to identify copy-number alterations throughout the whole genome. (B)

EpCAM-positive circulating tumour cells (CTCs) were enriched on a CellSearch platform. Total RNA was extracted and AR exon-junction RNAseq was

performed to determine AR splice variant expression. (C) To verify the presence of CTCs, the same enrichment was performed as in (B), but cells were

labelled, stained, and counted.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 2 ( 2 0 1 7 ) 1 9 2 – 2 0 0

194