compared to AS within a particular race (eg, the difference

in mean EPIC scores between RP and AS among AA men).

Subsequently, we are able to formally test the interaction

between race and treatment by estimating how the effects

of treatment varied by race/ethnicity (eg, the difference in

mean EPIC scores between RP and AS among AA men

subtracted from the difference in mean EPIC scores between

RP and AS among white men, which is the DID). Using this

systematic approach, we were able to precisely test the

race-treatment interaction for all patient-reported func-

tional outcomes after prostate cancer treatment.

Other studies have examined the racial variation in

patient-reported quality-of-life outcomes after prostate

cancer treatment, but without testing the interaction

between race/ethnicity and treatment. Using the CaPSURE

data set, Lubeck et al

[17]demonstrated that significant

post-treatment differences in functional outcomes existed

between AA and white patients at 1 yr. Specifically, AA men

reported worse urinary and bowel function with corre-

spondingly worse bother scores at 1 yr after treatment.

However, unlike the current analysis, these models did not

adjust for baseline function or comorbidity. In a separate

prospective, longitudinal multicenter observational cohort,

the investigators found that AA men were more likely to

report better erectile function compared to white men at

2 yr after brachytherapy

[18]. However, this study and

many others in this space

[19,20]are limited by small

sample sizes of minority men, making their estimates less

reliable. Furthermore, these studies failed to test or even

allow for the interaction between race/ethnicity and

treatment; that is, these studies merely report what the

post-treatment differences are between races at a single

time point. In contradistinction, our study comprises a large

cohort of AA and Hispanic men. Furthermore, because our

study uses AS as a comparator, we were able to estimate

how the effect of treatment (as compared to AS) varies by

race/ethnicity. This approach allows more accurate estima-

tion of the patterns of risk for minority populations.

Despite these novel data, several limitations should be

acknowledged. First, clinically significant differences in

EPIC domain scores are not firmly established. We used

published thresholds when interpreting these data

[12] .Second, the racial classifications used in this study

are almost certainly inadequate for fully describing each

person’s true racial and ethnic identity, and may not fully

capture significant racial, social, and cultural distinctions.

Moreover, and more importantly, this racial/ethnic group-

ing is a fairly arbitrary construct. Our analysis does not

acknowledge the variability within each group; the

individuals’ characteristics may be much more important

than race/ethnicity. Third, this is an observational study,

and unmeasured confounding, such as differential clinician

experience, access to high-quality care, or use of pelvic floor

rehabilitation, may give rise to biased effect estimates. To

address these concerns, the CEASAR study contains a

comprehensive set of patient-level variables, which, in

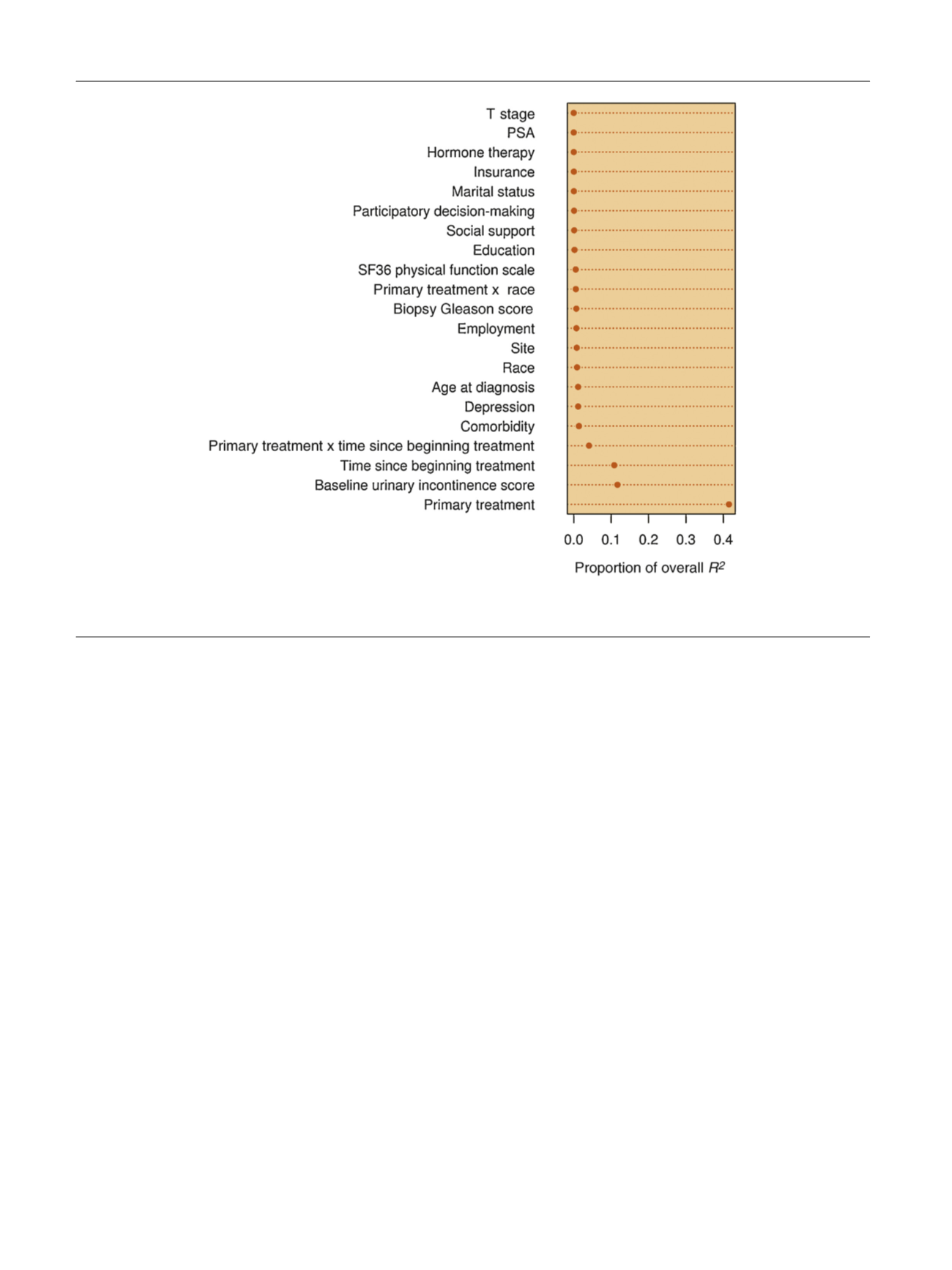

[(Fig._1)TD$FIG]

Fig. 1 – Proportion of overall

R

2

explained by different factors and interactions. PSA = prostate-specific antigen; SF36 = Short-Form 36-item

questionnaire.

E U R O P E A N U R O L O G Y 7 2 ( 2 0 1 7 ) 3 0 7 – 3 1 4

312